Part 1 of this lesson is available here in case you missed it.

Now that we’ve talked about haunted houses, let’s dig into a few of the mainstream theories about what addiction is and why it happens. There’s no single explanation of why a person becomes addicted to alcohol—it’s not a clear-cut process like getting pregnant or becoming a vampire.

I wrote this chapter because I found that it was helpful to have a baseline understanding of these theories because there are multiple ways to think about addiction, and some of these ideas resonated with me more than others.

An overview of mainstream addiction theories.

Alcohol use disorder (AUD) is a pattern of problematic drinking that runs on a spectrum of mild, moderate, to severe levels of alcohol dependence. You may have heard it referred to as “alcoholism” but I’m going to call it by the clinical term, AUD, which is also what the DSM-5 calls it.

The disease model.

The idea of addiction as a disease is used in AA and other 12-step programs, as well as historically in government programs like the US National Institute on Drug Abuse, SAMSA, etc., which is why it’s the one most people know about. “Alcoholism” is defined as a chronic, relapsing brain disease, which essentially means that once you have it, your brain has changed and you are an alcoholic forever.

If you think this sounds kind of unfair, I agree with you. However, the disease theory was still a big improvement from the previous theory of addiction, which saw drinking as a result of bad choices, moral failure, and weak character.

AA defines the disease as having 3 parts: a physical allergy, a mental obsession, and a spiritual malady. The physical allergy refers to cravings, as well as how it’s impossible to stop drinking once you’ve started. The mental obsession is pretty self-explanatory, and the spiritual malady means that there’s a god-shaped hole inside of you that you have been filling with booze and you are restless, irritable, and discontent.

Perhaps you are thinking, “But I can stop drinking after I started,” or, “My drinking has nothing to do with god or spirituality,” both of which are issues a lot of people have with AA and why they stop going or never go in the first place.

However, there are quite a lot of people who identify with having a disease, and it’s been helpful for their recovery. And I’d like to be clear: I am not saying AA is bad. I got sober because of AA. So if it is working for you, please don’t think I’m ridiculing you. It’s a program that literally saves lives. All I’m saying is that each person should have a choice in how they recover.

It’s kind of like the old “Indian burial ground” haunted house explanation we talked about in Part 1. For a long time this reasoning made sense and most audiences never questioned it. But once you dive in—and get input from Indigenous film scholars—you realize that this explanation leaves out a lot.

When I started going to AA, I didn’t know that there were other addiction theories! I already considered myself to be a broken human, so it was no trouble to accept that “my brain had a disease.” But over the past ten years, I’ve come to learn that AUD and recovery are a bit more complicated than I initially thought.

Biological models.

I used to think that people are predisposed to have AUD due to genetics. Because I have many family members with addiction issues on both sides, this made sense. And it’s true, addiction does run in families. It runs through communities, too.

But again, it’s not as simple as blaming your genes. For one, people with not-addicted families can turn out to have a drinking problem, and people with super addicted families can turn out to not have any alcohol issues. It’s also unfair to say someone is doomed to have addiction issues just because their parents did. There’s also quite a few environmental and societal conditions that perpetuate addiction within larger communities—more on that later.

Biological models of addiction say that our genes can make us more susceptible to addiction, but our brains play a bigger role. Dopamine release factors in, which explains tolerance (having to drink more to get the same effect) and withdrawal.

This is helpful for understanding what’s going on with your brain in medical terms. So if you’ve ever found yourself drinking again after vowing that you would stop forever because you had a nightmarish, diarrhea-filled hangover, now you know the science behind it.

Environmental theory.

This theory explains addiction as a result of what’s around us, what we learn, and how we’re conditioned. This can be everything from our families, to our peers, to what we see on Instagram.

Our environment is a social determinant of health, and it plays a huge role in our physical and mental wellbeing. In regards to alcohol addiction, growing up in a home with drunk parents, no supervision, and easy access to liquor could help explain the origins of person’s drinking problem. For another person who grew up with parents who didn’t drink, their dependency on alcohol could have started during the stress of the pandemic. Or, it could be someone works in a place with a big drinking culture and getting drunk is a regular part of their routine, which is a trope on many Korean cop dramas. It could also be something different entirely—it all depends on the person. The point is, we’re affected by what’s around us.

Psychodynamic model.

The psychodynamic model suggests that addiction is a defense mechanism and form of self-medication. A defense mechanism could mean getting a little tipsy on a first date because you’re nervous, or it could mean having to drink/smoke weed/take Xanax every day in order to face other people. And using alcohol as a form of self-medication comes pretty naturally. It’s why people get wasted after painful events like losing a job or getting dumped, and it’s also why they “maintenance drink” when they’re feeling unhappy, lonely, frustrated, etc. for a long period of time.

There’s also the fact that drugs and alcohol are often much easier to obtain and faster acting than finding a therapist in a broken health care system. That’s why you see slogans that say things like “Beer: it’s cheaper than therapy!” written on sandwich boards outside of bars or on wine-mom gifts. It’s a joke…but it’s also kind of true. Drinking is a way to control one’s emotions. The problem is that eventually, we lose this control.

Biopsychosocial model.

And now we come to The Shining of addiction theories—meaning there’s a little bit of everything in the biopsychosocial model.

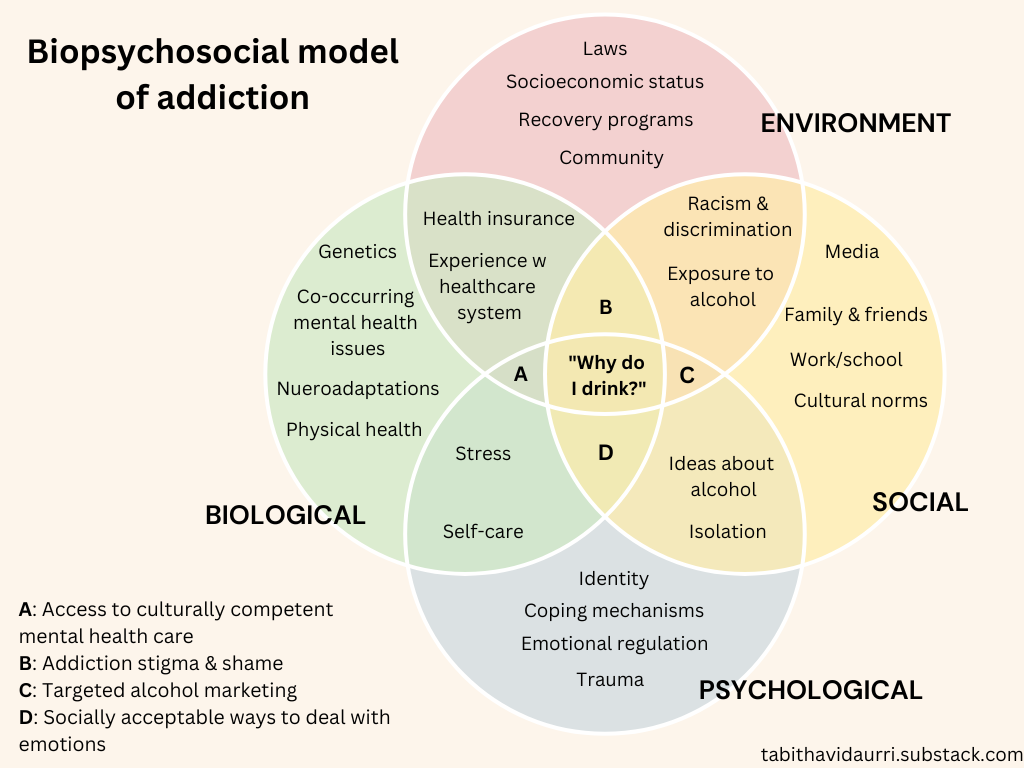

It covers the biological part about neural pathways and genetics, it covers the psychodynamic elements like depression, anxiety, past trauma, etc., and it takes a social element into consideration as well: where you are, what you believe, what your family and friends are like, how you were introduced to alcohol, and so on and so forth.

“The multifaceted disorder needs a multifaceted conceptualization, and we find that in the biopsychosocial model of addiction (Marlatt & Baer, 1988). Rather than pinpoint the one thing that causes addiction, we now understand that a constellation of factors contributes to a person being more or less at risk for addiction.” – Amanda L. Giordano Ph.D, LPC

And to illustrate some of the stars in the constellation of factors, I have made this Venn diagram.

I know, this diagram is kind of a lot. And if you’re like “Ug” right now that’s ok, I’m going to clarify everything with some examples in the next chapter.

The takeaway here is:

The causes of addiction are complicated.

Treating addiction requires an approach that considers all of the causes.

I couldn’t pinpoint a single reason why I drank, and that’s because there were a bunch of different reasons. There was a biological component at play of course—if you keep ingesting addictive substances in order to make yourself feel better you will become dependent on them. That can happen to anybody. But why I was more susceptible to getting addicted in the first place is more complex.

Some reasons were unique to me, like who I am, how I grew up, and what I think about myself, other reasons had to do with stuff people in my generation all had to deal with, and then some reasons were much bigger like how it’s really hard to get decent mental healthcare in America, especially when you don’t have money or insurance. There’s also who I hung out with, how much I slept, my identity as a woman, etc., etc., etc.

Using this model isn’t about blaming people or things for your drinking. (Believe me, I tried doing that and it didn’t work.) Nor is this about listing all the ways in which you and your life are fucked up. (Again, been there, done that, bought the t-shirt.)

Taking a holistic approach to your recovery is about understanding what’s been going on with you, figuring out what you need, and how you can go about making positive changes that work for you.

Next up in Part 3:

Where are you going with all of this, Tabitha? How is this going to tie back to haunted houses? Tune in next time to find out!

Love the creativity (and usefulness) of this series, Tabitha! Also love that you explore addiction from multiple angles and with tons of nuance and inclusivity.

I didn't get sober through AA and do not subscribe to the "disease" model of addiction. Still, I fully support others who want or need that approach and model. And I greatly appreciate folks like you, who recognize that there are many facets to addiction and who embrace a holistic approach to recovery. Thank you!